Growth from Trauma

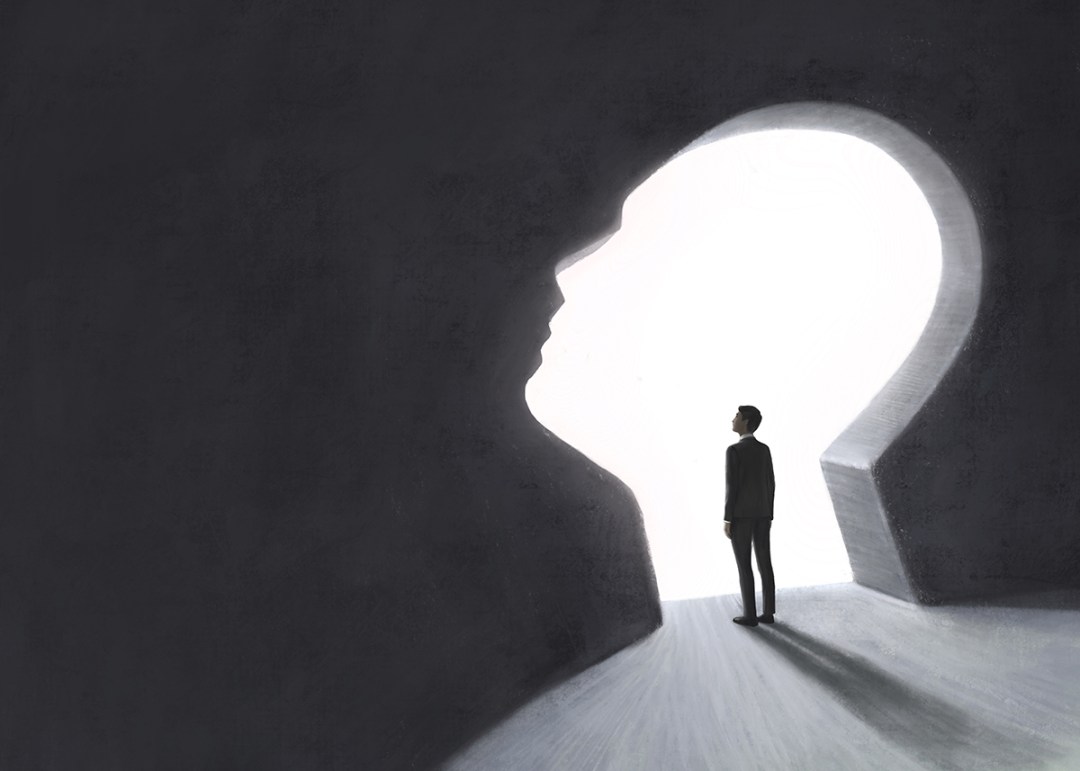

If we can seek meaning out of our suffering, we will find hope and our future

How is it that in the midst of trauma some seem to find meaning and new hope? If we can ease into suffering, instead of trying to fight it, we will feel more hopeful and in control. And perhaps even be able to see into a new future.

Covid-19 crisis

Over the last eight weeks during the COVID-19 pandemic, all around the globe we are in various stages of the crisis brought on by the same event. What we see and hear all around is negativity and fear. Some are experiencing financial panic and loss, others emotional. Yet I have been observing that some people, including myself, seem to be thriving. For a while I felt bad that I wasn’t suffering. Of course I have been staying at home and have had my life limited just as much as everyone else. Yet I was getting on with life quite happily whilst others were more traumatised.

This wasn’t happening because I am in a more privileged position, financially or otherwise. So what was going on?

We can all learn from trauma

Like every other human being on the planet I have had my fair share of trauma. In fact some of it happened just before the coronavirus crisis. And this is what has made all the difference. Six months ago I came out of hospital with a 10 inch scar and 40 plus stitches in my head. You see during the last two years I was diagnosed with a possible cancer, almost needed a hysterectomy, had a new diagnosis for a large tumour on my head and needed two operations.

A crisis makes us feel alive

My first operation was gynaecological and involved the removal of benign tumours and lumps. It all went well and I actually enjoyed the 10 day stay-at-home time. A good friend and neighbour had also had a minor operation we self-isolated together, albeit virtually. We provided moral support and consolation for each other. During the cancer scare I had to face some fear. Yet I came out of the experience filled with gratitude for the all-clear.

Nevertheless, during that time, a deeper trauma had begun to reveal itself. That some people seemed to forget I was there. I had expected that people would be there for me, enquiring with concern about how I was. Instead I felt somewhat lonely and isolated. But I quickly recovered, got back to work and forgot about it.

And another one

However, as soon as I had found normal again, I got a confirmation of another operation a few months away. This time for a tumour on my head which I had for 10 years but which had been growing. Denial came in handy this time. I was convinced it was a type of cyst and the operation would be a simple incision. Despite my surgeon telling me it was probably a haemangioma. The latter meant a large coronal flap incision and two hour plus precision operation, with likely facial paralysis afterwards from which I may or may not recover. I just did not entertain the idea of that. I was calm and collected, even when waiting in the Royal Stoke Hospital for four hours on my own. Even when the nurse came round and said “you are going last as you are his big operation today.” Denial is a fabulous thing.

When we face our fear we find our power

All was well, I absorbed myself with a book and with yoga mantra and breathing techniques. But let’s not forget that my biggest ally was denial. When the orderly came to wheel me off to the theatre, I was laughing and joking with him. In the pre-theatre room, it was supposed to be straight into surgery after the general anaesthetic. But they had brought me down 15 mins too early as the last op had overrun. Suddenly 15 mins felt like it would be five hours. I told myself I was doing ok. I met my surgeon briefly and told him not to leave his keys or anything in my head. This man who I got to know reasonably well over the 10 years was normally the one playing these jokes on me. He pretended to find it funny. My intuition told me he was nervous or distracted. I tried to turn my head to look away every time the cold metal double doors in front of me opened to reveal the pristine white and steel of the theatre itself. I tried to appease the nurse when she said “I hate it when this happens, it always makes people more anxious!”. Not me, I said, I’m ok.

They started to fuss and put the cannula in and I could feel sweat on me. Then, they put sensors on my chest, hooked me up to a machine and could hear my own heartbeat. Just like on those hospital dramas. ‘S***!’ I thought, ‘I’m in hospital!’ Then the room started swimming. A nurse in front of me said, I think she is having a fit. Another one said, no you’re not darling you’re just passing out aren’t you.’ I think I managed to say yes before everything faded. In that moment, all my fears could no longer be repressed.

Finding resource in the midst of trauma

When I came round they were panicking a bit. I didn’t need their reassurances as this was fairly familiar territory for me – it wasn’t the first time I had passed out in a panic attack. But I now felt stronger. However, the anaesthetic looked worried. “The surgeon needs to know if you are ok to go ahead?” I felt I should be asking them that! Then this power rose up in me, even in face of the full realisation of what was about to happen and I surprised myself when I said, unflinchingly: “there is no way I am going back into the ward now, I’ve nearly done your job for you anyway!” (laughing). And so I went in.

Four hours later I came around. It had been a two hour plus operation on a huge haemangioma which had lodged deep in my temporalis muscle and temporal cavity. But my surgeon got it all – albeit with a (very neat) 10 inch scar and 40 plus stitches.

Earlier trauma triggered

In my two week recovery, the isolation once again reared its head. I coped by buying myself things. And pushed it away again. I went back to normal life, proud of my scar. However, this was my first full year of working alone after downsizing my once eight-strong business, to just me. It was only when I started to experience some strange anxiety that seemed to come out of nowhere and wouldn’t go away, that I sought some help.

This time I looked at psychoanalytical psychotherapy, because I knew that whatever was bubbling under was deeply unconscious and my defence mechanisms had it firmly defended. During this self-discovery I realised that, amongst other things, the isolation was triggering a very early ‘abandonment’ at a pre-verbal stage. I had spent six months working through this, and actually getting to a place of being truly happy and content working alone, when COVID-19 struck.

Post-traumatic growth

In a strange way, these previous traumas had been perfect preparation for me to benefit, even grow, during COVID-19. I now realised that Richard Tedeschi, Ph.D. and Larry Calhoun, Ph.D. have termed this “post-traumatic growth” but Viktor Frankl, my hero of many years, knew about this long before it was popularised in a trendy buzzword. Viktor Frankl was a renowned Austrian psychiatrist, neurologist, and also a holocaust survivor. He wrote ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’. He along with other philosophers, psychologists and thinkers, had a big impact on me when I was younger. And this quote of his stands out now: “When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.”

Lifelong life changes

I embraced my traumas before the coronavirus crisis. I worked hard on controlling that which I could control, changing the only thing I could. And that is myself. Amazingly during these last few months I have experienced unbridled energy and creativity. I have even set up a new creative business designing and making unique handcrafted jewellery and gifts made from the snakeskin of my five adorable creatures. Whilst I don’t expect this to provide a big income, it is a dream-come-true for me to finally find an outlet that I am passionate about for my artistic nature.

Apparently not everyone who suffers trauma experiences post-traumatic growth, but for those who do, the changes can be lifelong.

Growth from Trauma