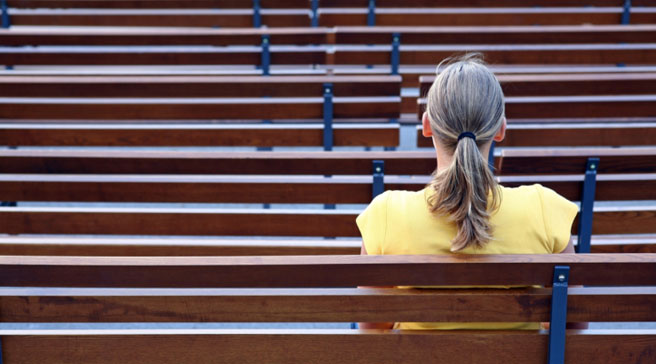

The loneliness epidemic

Loneliness affects one in 10 of us, according to a report out today, and for some the cure can be found in a garden shed

'Where has May gone?' I thought this morning, not for the first time this month. Opening my diary I can see exactly where: back-to-back weddings, a weekend in the country, lazy dinners with friends, and a couple of evenings in town with more pals.

But frankly, it’s all getting too much. Now I’m staring down the barrel of June wanting nothing more than a month of solitude, or maybe just a week, to be left alone with no one to call, email, have a drink with or invite round to dinner.

Perhaps I don’t really mean that. The weddings were lovely and dates with friends are always time well spent. Furthermore, I should be grateful for the people in my life since, according to a report out today from the Mental Health Foundation, Britain is in the midst of a loneliness epidemic.

One in 10 of us — young and old, women and men, rich and poor — admit to feeling lonely, while half of us believe that we’re all getting lonelier in general. No wonder when you think that between 1972 and 2008 the number of people living alone in the UK has doubled.

The report points to a number of reasons, including the decline of community, from closing post offices to living further away from our families, and the increased focus on work. But anxiety about loneliness is neither new nor is it a quintessentially British problem.

Back in 1950 three sociologists in the US penned the seminal The Lonely Crowd (a great title, don’t you think?), an examination of the post-war American character. The new American middle class, it stated, no longer felt ‘tradition-directed’ — law-abiding, community-minded, conforming to values of religion and the family — but ‘outer-directed’, defining themselves by what others have, earn, value and look like.

Friendship and family ties seem to have taken a back seat ever since. I read today that the average American has only two close friends to confide in, with a quarter saying they have no one to confide in, according to a 2006 study in the American Sociological Review. So much for having loads of Facebook friends.

It’s worse in Japan, where self-imposed loneliness is a devastating problem among its young people. A special syndrome — 'hikikomori' — has been identified, affecting more than a million Japanese. Sufferers withdraw from society, usually confining themselves to their bedrooms (in their parents’ houses) communicating with the outside world only via the internet.

Thankfully, things haven’t come to that in Blightly where you needn’t go far to see examples of how loneliness is being combated. The report singled out parenting site Netmums where, after contacting other mothers via the site, 10,000 women meet face-to-face each month, which can help to reduce the sense of isolation some new mothers experience.

But my favourite anti-loneliness story is the Men In Sheds project, created by Age Concern in Cheshire, where older men can get together in a community shed ‘to learn new skills, share existing skills and knowledge, and generally put the world to rights over a cup of tea'. Of course we all benefit from a quiet night in now and then, but nothing, not good telly, an instant message or even a good book, compares to good company. Looking back at my diary I realise this is something to savour and celebrate.