Interview with author Shelley Harris

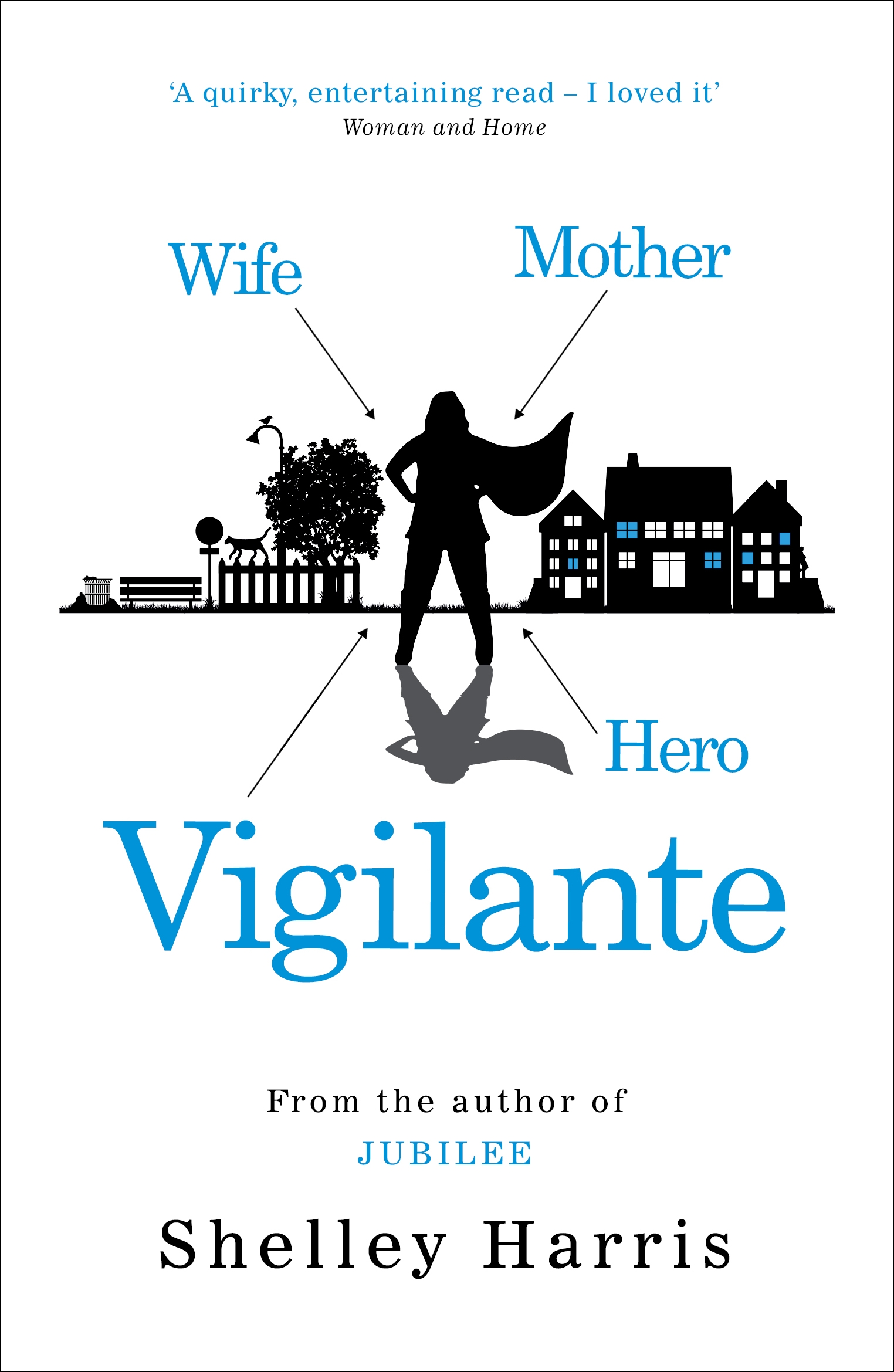

Author Shelley Harris put on a superhero costume and walked the streets to research for her new book Vigilante. Here, she shares her inspiration for the novel and talks about what it means to be a woman who wants to be extraordinary…

Vigilante is a fabulous read – a gripping narrative that starts light and gradually becomes darker, touching on such broad and delicate subjects violence against women, midlife crises, teenagers coming of age and sexism in comic books.

Jenny Pepper is frustrated by the limits on her life as a 40-something wife and mother to her distant, stroppy teenage girl. One evening, Jenny bravely steps in to save a woman in trouble and her world becomes exciting again. As she starts patrolling the streets, she feels alive. But then a real villain appears and her own daughter is in danger. As Jenny starts to see less clearly through the mask, she finds her fantasy life becoming frighteningly real.

Here, I ask Shelley Harris about Vigilante and what inspired her to write the novel.

What first gave you the idea for the story? Did the character of Jenny Pepper appear first – a middle-aged woman craving some excitement in her life? Or was it the need to protect our children in this seemingly scary world?

It was definitely Jenny who came first – and more precisely that feeling I think most of us have had, of looking at our lives and thinking: is this it? That was me, at 40. To shake things up – and I know this is going to sound odd, but stay with me – I started to cycle round my small town, leaving poems anonymously in shops, churches, parks, the library. What I didn’t expect was the incredible effect this had on my mood. It was astonishingly empowering. When I analysed it, I realised it was secrecy that was key. Small, secret good deeds can change the world for the person who does them, let alone the people who benefit from them.

So I thought: what if someone had a midlife crisis and coped with it by doing secret good deeds – huge ones, daring and scary ones? And what if, after a while, they can only cope with being themselves by being that other, secret hero? So Jenny was born.

You put on a superhero costume and walked the streets doing good deeds – exactly what Jenny does in Vigilante. What was that experience like? Did it help you envisage Jenny’s character more fully?

It was an incredibly useful thing to do. Getting right inside a character, feeling what they feel, is often the best way of understanding their experience. I learned how scared she must have felt when she stepped out in that costume, and therefore how desperately she must have needed to do so. I also learned how different everything is once you’ve got that mask on; that was the biggest surprise. The anonymity frees you completely.

I learned that, if you’re an invisible middle-aged woman, you become instantly visible in a superhero costume, which has all sorts of knock-on effects. I learned that ‘rescuing’ people can be patronising, and I learned that most danger doesn’t happen out on the streets anyway – it happens in private.

Just wearing the costume changed my outlook. On the way to my book launch party, I had it on under my coat, and as I travelled the Tube I realised I was looking out for trouble so I could step in! No mask on yet, and no-one else could see the cape, but I knew I was wearing it, and spent the journey scanning the carriage for danger!

One quote I love was when Jenny thinks: “what a poor substitute it was being a Bond girl, when all we want to be is James Bond.” It’s something every woman can relate to. In Vigilante, did you want to find a way to deal with the themes of sexism and the limits of how women are seen and treated?

That wasn’t how it started: I began with Jenny. But it’s impossible to convey the experience of a middle-aged woman – of any woman, actually – without bumping up against those imposed limitations and the ways in which we try to challenge them, subvert them, live with them – all those coping mechanisms women have had to develop.

Vigilante touches on a broad range of topics, from misogyny in comics to the sexualisation of schoolgirls, and parents’ helplessness when they want to protect their children but don’t know what to do. Did you consciously set out to cover all these themes? How did you plan the novel? Did you know the ending before you wrote it? How did you see Jenny’s life changing by the end?

Although I care very much about all those things, I didn’t set out to cover them in the book; they came up because they do come up for us, don’t they? It’s an old feminist saying that ‘The personal is political’, and that’s what I really found as I got to know Jenny. How can you mother a girl without becoming horribly aware of how parts of our culture sexualise kids? That coy ‘all grown up now’ caption on the front pages of national papers, those ‘Future WAG’ T-shirts in toddler sizes. It’s not an abstract theory; it’s something that impacts our lives directly.

As for the ending, I had it in mind right from the start, and it shifted only a little as I wrote it. I planned the rest of the novel very tightly but discovered – inevitably – that characters don’t obey a plan. I suspect most novels come into being more messily than we like to imagine! I’m trying hard to avoid spoilers, so as far as Jenny’s ending is concerned, I wanted her to define herself, after all those years being defined by other people. I wanted her to discover a greatness within her, amidst the mundanity that most of us live with.

The theme of identity in the book is strong. Jenny says: “All I’d wanted was to wear the uniform and go out into the streets without anyone knowing who I was, so that I could decide for myself who I might be.” I think she finds a way back to herself and also shows her husband and daughter that she is more than the limits they imposed on her – do you agree? Can she be a wife, mother, herself, and a hero? Can women truly be all these things?

Yes, I completely agree with you about Jenny finding a way back. And your question’s really interesting, I think. What our culture means by ‘Wife’ and ‘Mother’ (especially the latter) are incredibly narrow definitions. We are, of course, entirely capable of operating multiple roles, but I think we have to redefine those roles ourselves rather than take what we’re given. I don’t think it actually is possible to be fully yourself and be a ‘mother’ in the way our society expects us to. So: it’s up to us to be our own sort of mother, our own sort of hero. And always completely ourselves.

To find out more about Shelley Harris and Vigilante, click here and follow her on Twitter @shelleywriter

Photograph: Julie Hoggan