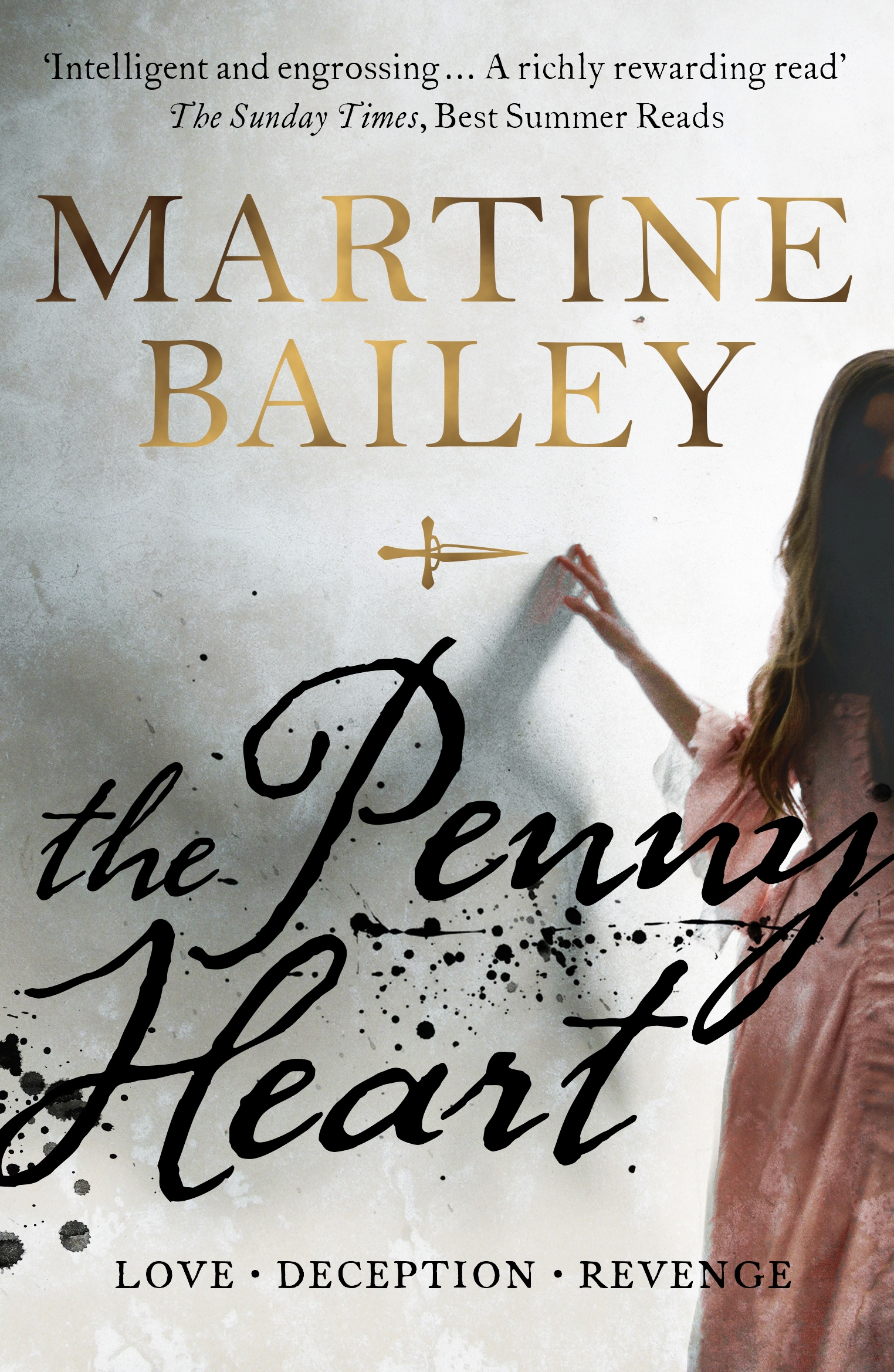

New fiction: The Penny Heart and interview with author Martine Bailey

The Penny Heart is the second book from 'culinary gothic' author Martine Bailey. Here, we review the book and ask Martine a few questions about it…

Set in the late 1700s in England, Australia and New Zealand, the book begins with Mary Jebb actioning the confidence trick that will send her to the gallows… which she escapes, instead being sent to the unforgiving penal colony of Botany Bay. But Mary is determined not to be forgotten, sending two pennies, engraved with a promise to the two men who sealed her fate.

Timid artist Grace Moore jumps at the chance to marry handsome gentleman Michael Croxon, happy if only to get away from her drunken father. But when Grace takes on a new cook, the two penny heart love tokens reveal she is tied to a world she didn’t know existed… a world of deciet, double-crossing, revenge and murder.

Atmospheric with rich period detail and a thrilling narrative that keeps you turning the pages, A Penny Heart is a brilliantly immersive read, with fascinating characters and an involving story that interweaves the darkest of human experiences with the courage and faith that helps us survive.

The novel was inspired by the Penny Heart tokens created by convicts as keepsakes when they were transported to Australia. How did the character of Peg grow from this point? Or did you have a vision of her first?

In An Appetite For Violets, I had written about a strong but essentially good-hearted cook who is taken on a sinister journey to Italy. When I was asked for an outline of a second novel, I was living in New Zealand and knew at once that I wanted to write a darker version of a mistress and servant’s relationship.

As I walked along the empty beach near our house-swap home, I began to visualise Peg as a firebrand exiled to ‘the ends of the earth’. The local history I discovered, of the prison colony across the sea at Botany Bay and local stories of European women captured by Maori, combined to make Peg a woman living at the extremes of both geography and morality.

Penny Hearts, or love tokens, seemed an apt symbol of Peg’s defiance. They were Georgian copper pennies, smoothed and engraved with images and personal messages, left behind with families and sweethearts in Britain. I’m always interested in how history is being constantly reinterpreted, and though they were once treated as shameful, Penny Hearts are now valued as authentic messages of love, defiance and anger. For most of the novel, Peg wears her Penny Heart on a ribbon beneath her bodice as a reminder of her resolve to take vengeance.

Did you do much research food-wise as you did in your first novel, An Appetite For Violets, or was the research different this time?

To write my first novel I learned the basics of Georgian cookery, so this time the research was far less intense. Instead, I learned to make historic sugarwork with Ivan Day when I returned to the UK. I became fascinated by tiny sugarwork decorations, such as a miniature bed to be placed on a wedding cake and a tiny cradle and swaddled baby. These ‘memorialisations’ of important events struck me as powerful Gothic symbols showing the fragility of hope in the book.

I also researched secret remedies, poisons and aphrodisiacs. I spent a long time looking for recipes until it dawned on me that of course these were often secret! But there were hints of old wives’ narcotics in home remedies such as Poppy Drops, sleeping draughts and an ancient recipe for Twilight Sleep that was once used to help women in labour.

In the Antipodes I tried lots of different foods, including meat cooked in a hot-stone hangi pit, along with grubs, damper, sea snails, crocodile and kangaroo. I also went out to Parramatta, Sydney, where the first Europeans began farming, and hunted down old recipes for potted possum, wattle tea and witchetty grub soup.

The events that Peg has to endure are horrific and shape the person she becomes. Did you find it a good channel to address how women suffered at this time in history? Was it difficult to write about?

My aim was to tell a dramatic and entertaining story, but I also wanted it to contain authentic historic truths. I found it difficult to write about the more vulnerable convicts, especially the very old or young. We can get glimpses of them on Penny Hearts, such as Mary Eater and her barrow of fruit or vegetables or another woman releasing a dove beside an anchor of hope and the words ‘I Love till death, shall stop my breath’. We know from surgeon’s reports that as many as a quarter of women convicts also had tattoos that shared this imagery of chains, anchors, birds and mythical figures.

I felt it was important to bear testimony to women who have been misrepresented. I immersed myself in accounts of the first fleet to Australia and tried to follow the histories of a number of women, especially Mary Bryant who famously escaped by boat and returned to England. Some of the historical facts are almost unbelievable, for example the night of the ‘Great Storm’ when a sexual free-for-all was allowed because it was ‘only to be expected’ after months of male incarceration.

As a reader, I admired Peg for her courage and survival skills but also detested her for her greed and disregard for other people. And I saw her love of making sweet desserts as compensation for her sour character! How do you feel about her?

I confess I became quite mesmerised by her. I grew to admire her courage, while also pitying her, as she has huge lacks in terms of empathy and morality. But then again, like many sociopaths and psychopaths, she has not been adequately nurtured.

Her ‘hunger’ grew from a phenomena I’d heard about when starving prisoners develop an obsession with recalling food and recipes. I’ve also noticed a preoccupation with hoarding in people who have had bad experiences during war or imprisonment.

I think Peg’s fascination with sweet desserts is a kind of self-love, where she obsesses with having plenty of all the good things she has had to live without.

I did struggle with which of the two women, Grace or Peg, should prevail in the end. I wanted to keep the balance quite equal, although I have noticed some readers really root for one or the other.

How you feel about Grace? She starts off timid, naive and trusting and by the end, she is changed but her core values remain the same despite what she goes through.

Superficially, I’m more like Grace – quiet and artistic. She was in part inspired by cherished objects of affection I found in settler homes, such as woven locks of hair, scraps of fabric, and portrait miniatures. But then again, I’m more determined than people would ever think, and very interested in justice and fairness, and sympathise with the underdog.

Grace has her troubles, as a propertied but powerless woman, vulnerable to the greed of her husband. But clearly the balance of fate weighs more heavily against Peg, who is poor and parentless and exposed to a brutal life. I had to draw on different parts of my personality to write both of them, but I always intended that Grace would need to ‘wake up’ from her sleepwalking life. That she finally stands up and fights for her core values, makes her in my mind just as brave as Peg.

It was clever of you to tell the story from both Peg’s point of view and Grace’s, as it kept a lot of the mystery of the story under wraps. Was this a technique you knew would work with this story? Or did you experiment with different narrative styles?

In my own reading, I love twists and turns that arise from two or more different characters telling their story, for example Belinda Bauer’s Blacklands, Barbara Vine’s A Fatal Inversion, and of course Sarah Waters’ Affinity, a tour-de-force of historical crime.

When I planned to show upstairs and downstairs with very different secrets, I knew at once it had to be told from both points of view. I love crime fiction, so knew it was a good device, to keep each character operating in the dark and let the reader actively piece the narrative together. In my researches into the 18th century, I also come across examples of employers fearing sinister servants and that struck me as a very fraught situation.

It was a tricky book to write. I use mind maps for each chapter and ask myself what each character’s grasp of events must be at each stage. When I was about halfway through, I planned key scenes by drawing a line down the centre of a page and writing what was really going on, on one side, and what the reader and other characters could see on the other. At one point I wondered how on earth I could resolve it all but my brain cells just about coped!

How did living in Australia and New Zealand help with the understanding of the countries’ history?

In 2011 our son Chris and his partner were caught up in the Christchurch earthquake and though thankfully unharmed, we speeded up our application to take an extended trip there. For our first year, we house-swapped on New Zealand’s remote East Cape, in a house overlooking the Pacific. The sense of distance and disjunction from Britain were an immense influence on The Penny Heart.

My husband Martin was teaching Maori youngsters, so I was fortunate to get a deeper view of the strong local traditions of singing, tattooing and celebration around the meeting grounds or Marae. After our first year, we travelled around more, spending time across the Tasman Sea in Australia.

We were always made extremely welcome in New Zealand. We had the chance to live and work in an eco-house near the black beach at Muriwai, Auckland, which became the shore where Peg is shipwrecked. The New Zealand Society of Authors also gave me a mentor who provided terrific feedback on the New Zealand scenes. I love the Antipodean ‘can do’ attitude and still miss the free modern libraries with wi-fi, coffee shops and the best ocean views in the world!

I could have done much of the research on the internet, but the parts based on real experiences – the shimmering heat of the Australian bush, the human stories of people searching for better lives at the ends of the earth, and the singing and ceremonies of the Maori – seem to me to make The Penny Heart a more vivid book.

I love how good and evil are balanced in the novel; the colonies are both horrific as in Peg’s experience and hopeful as in Anne’s; London is both a refuge for Grace and a threat… how important was it for you to show different sides to the same place, the same story?

To me, historical fiction is in part about taking the long view – and progress is often painful. Many people suffered hardships in the 18th century, but there were also powerful positive forces released as Britain became a modern nation. The poor lived cheek-by-jowl with the vastly wealthy, which partly led to a crime wave as cities developed. Yet this, in turn, led to the birth of colonial Australia, starting as an experiment to house Britain’s criminal underclass, but leading to the creation of a dynamic new nation.

On a personal level, like many people living abroad, I felt I became two people: the new adaptor trying to learn and cope, and the old self haunted by thoughts of family and ‘home’. Some of my richest experiences were hearing people’s stories; the Maori woman whose son had murdered his brother, the migrants from China struggling to reinvent themselves, and the locals who were raised in the forest, washing in the creek.

Can you share anything about what you’re working on next?

After crossing Europe to write my debut, and then roaming the Antipodes for The Penny Heart, I felt ready to stay at home in Cheshire for a while! I knew I wanted to write a murder mystery and set it against the rural festivals and seasons of England. The Starry Almanack is based on old-fashioned almanacks, little pocket books that were once second only to the Bible in popularity. They are fascinating mixtures of calendars, astronomy, riddles and predictions.

To get into character I recently went to the Acton Scott Museum, where the BBC’s Victorian Farm was filmed. I had a wonderful time pretending to be a farmer’s wife, dressing up and making butter, feeding lambs and sewing around the table. Just as my first two books are written in the style of recipe books, the new book is interspersed with 18th-century riddles. I am just completing the final chapters and have absolutely loved the whole process!

The Penny Heart is published by Hodder & Stoughton and is a Sunday Times Best Summer Read, available in paperback (£8.99) and audio book. It is also published by St Martin’s Press in the US as A Taste For Nightshade.

For more about Martine Bailey, visit www.martinebailey.com and follow her on Twitter @MartineBailey and Facebook @MartineBaileyWriter